In his article, Robert J. Talbot broached the history of Canada Day celebrations by using the dramatic thread of the English-French linguistic duality. As a sociologist of art and Wendat, I will discuss the History-Show in Kanata’. Doing so will allow us to follow the evolution of the relationship between English Canadians, Quebecers and indigenous peoples. The 150-year history (1867-2017) can be divided into three periods:

1. The erasure of the “savages”, despite their resilience, for which the year 1867 is a marker;

2. The recognition of Aboriginal people today and the decolonization of the stereotype of the Indian as the reverse of the White Man: the beginning of a Political History for which the year 1967 is the landmark date;

3. Aboriginal self-affirmation, an ongoing process in 2017, instantiated in Spectacles Without History, which reflect the dislocation of the dominant Quebec and Canadian national identities.

1867

The foundation of Canada contains a tragedy that turns on the quasi-disappearance of its First Peoples for whom the federal government gained exclusive responsibility in 1867 [1]1Journal of the Canadian Historical Association

"Clearing the Plains" and Teaching the Dark Side of Canadian History

2015. The various iterations of the Indian Act—from 1857 until 1951 – systematized reductive views and instruments of cultural genocide such as the residential schools. Aboriginal languages were repressed. And just as our ceremonies, dances, and feasts were declared illegal, the first images presented by the White Man to the “Savages” were those of the scaffold: Louis Riel and eight warriors of Big Bear and Poundmaker were hanged in 1885.

The Conquest was complete. So began the appropriation of artifacts and knowledge. Aboriginal symbolism entered into popular imagery and became a basic plot-line for the nascent culture of the spectacle. Whites played Indians: this is the Emily Carr and Gray Owl syndrome [2]2Canadian Studies

Hearing the Voices in Armand Garnet Ruffo’s "Grey Owl: The Mystery of Archie Belaney"

2006.

Enter now the Wild West Show—that included William Cody, alias Buffalo Bill, Sitting Bull and Gabriel Dumont [3]324 images

Une photo mythique a 125 ans cette année : Prise de guerre

2010. Stereotypes of cowboys and Indians, the Indian wise-man or the savage warrior proliferated in photography, cinema, television, fairs, major exhibitions and commemorative ceremonies [4]4Journal of the Canadian Historical Association

Appropriating the Past: Pageants, Politics, and the Diamond Jubilee of Confederation

1998.

We saw them during Quebec City’s tercentenary in 1908 when the History-Show [5]5Toronto : University of Toronto Press

The art of nation-building : pageantry and spectacle at Quebec's tercentenary

1999 was recreated in live pageants on the Plains of Abraham [6]6Cap-aux-Diamants

Les «pageants» : l’histoire mise en scène

1993. The Indians of the surrounding area were in such an impoverished state that English organizers called upon local Indians to replay the scene of the massacre of Dollard des Ormeaux à la Buffalo Bill. This was by far the best pageant: for once, the Indians won [7]7Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française

Annaotaha et Dollard vus de l’autre côté de la palissade

1981!

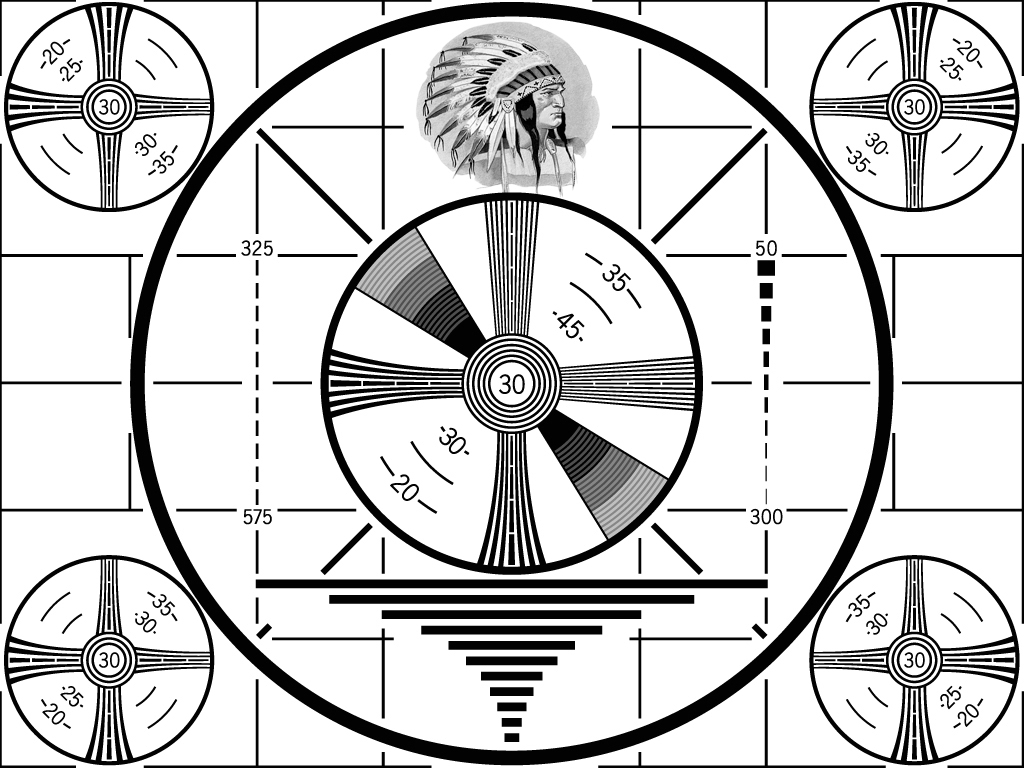

In reality, it was not until 1951 that the prohibitions on our feasts and ceremonies were lifted. A year later in 1952, however, the profile of an Indian in a headdress on a shooting target became first televised image on the CBC. As Marshall McLuhan would say: The Medium is the message!

1967

In 1967, Aboriginal peoples featured on two of the largest stages yet assembled. Their representations marked the resurgence of the self-determining Aboriginal as a third party along with the Canadian federalist and the Quebecois separatist.

The process of decolonization, which started with the Indian Government of North America project initiated by William Commanda, Jules Sioui and Origène Sioui in 1944-1953 [8]8Ottawa: Commission royale d'enquête sur les peuples autochtones

Les Sept Feux, les alliances et les traités autochtones du Québec dans l'histoire

1996, then moved to the forefront. In Vancouver, a crowd of 32,000 heard Chief Dan George’s famous Lament for Confederation that foreshadowed a great career in cinema [9]9Journal of the Canadian Historical Association

"It’s Our Country”: First Nations’ Participation in the Indian Pavilion at Expo 67

2006.

Oh Canada, how can I celebrate with you this Centenary, this hundred years? Shall I thank you for the reserves that are left to me of my beautiful forests? For the canned fish of my rivers? For the loss of my pride and authority, even among my own people? For the lack of my will to fight back? No! I must forget what’s past and gone.

Chief Dan George, 1967

In Montreal, at Expo 67, Man and His World, the most celebrated of the Universal Exhibitions, an Indian Pavilion, independent of those of Canada and Quebec, offered a distinctive architecture—the tipi—, great works of contemporary aboriginal artists led by the artist-shaman Norval “Copper Thunderbird” Morrisseau, and theme rooms that showed the world the problems of reservations in Kanata‘. The Spectacle became Political History [10]10Anthropologie et Sociétés

Un Wendat nomade sur la piste des musées: pour des archives vivantes

2014.

2017

The historic amnesia seemed to fade at the beginning of the new century. For the first time, in 2001, the Great Peace of Montreal of 1701 was celebrated [11]11Vie des arts

"Histoire d’un traité de paix…", exposition au musée Pointe-à-Callière, Montréal

2001. In 2008, during the 400th anniversary of the founding of Quebec, the Huron-Wendat First Nation was recognized as the historic host [12]12Inter

Expositions «sous réserves»: les avancées à Wendake et à Mashteuiatsh

2009. In 2010 in Vancouver, however, while an Inuit inukshuk had become the symbol of the Olympic Winter Games [13]13TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies

“A Portrait of This Country”: Whiteness, Indigeneity, Multiculturalism and the Vancouver Opening Ceremonies

2012, the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development was in the process of sending body bags to First Nations’ reserves in response to the worst outbreak of influenza A (H1N1) seen in the country [14]14Inter

Au regard de l’aigle, les Indiens sont partout et nulle part!

2009!

And now it is 2017. A new division appears on the horizon. On the one hand, we have the commemoration of the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation and 375th anniversary of the founding of Montreal that have been conjoined in a series of Spectacles Without History involving: technological prowess (the Jacques Cartier Bridge illuminated for 40 million dollars), oversized street art (the fables of the Giants in Montreal and Ottawa) or small fragmented stories (the controversial television series, The Story of Us, on CBC, a private, Americanized show at the Bell Center, the battle of the Patriotes’ flags, the Maple Leaf and the Fleur-de-lis flags at Quebec, the television nationalism of hockey games and beer vendors—a “Canadian game” [15]15International Journal of Canadian Studies

Playing Promotional Politics: Mythologizing Hockey and Manufacturing “Ordinary” Canadians

2011).

On the other hand, we are witnessing the transformation of local communities in the pursuit of social justice through education and the revitalization of languages, Pow Wows and traditional customs. To these we can add national social (i.e. Idle No More/Plus jamais l’inaction [16]16Nouvelles pratiques sociales

Idle No More: identité autochtone actuelle, solidarité et justice sociale. Entrevue avec Melissa Mollen Dupuis et Widia Larivière

2014) and anti-globalist movements for the protection of Mother Earth. Pipelines departing from Fort McMurray, passing through “Standing Rock” and the struggle against the deforestation of the “Indios'” territory in Amazonia, the ecosystemic resistance to the exploiters and polluters of Nature, provoke aboriginal peoples’ opposition. Reparation takes precedence over reconciliation.

Read more

James Daschuk, La destruction des Indiens des Plaines. Maladies, famines organisées et disparition du mode de vie autochtone, trad. Catherine Ego, Québec, Les Presses de l’Université Laval, 2015.

François-Marc Gagnon, Chronique du mouvement automatiste québécois, 1941-1954, Lanctôt Éditeur, Montréal, 1998, « Protestation contre la loi du cadenas », p.573-576. Read

Bruno Cornellier, La « chose indienne ». Cinéma et politiques de la représentation autochtone au Québec et au Canada, Montréal, Nota bene, 2015.

Jean-Jacques Simard, La réduction. L’autochtone inventé et les Amérindiens aujourd’hui, Québec, Septentrion, 2003.

Translation: Peter Keating